Navigating the Complexity of Alzheimer’s

Dementia is a uniquely terrifying prospect for most of us, more frightening even than the dreaded C word. Cancer is an enemy to be battled, but Alzheimer’s disease is a slow, creeping tide – there is no battle to be fought, and there are no survivors. It strikes at the heart of who and what we are – erasing our memories and stealing our very identity. As a society, fear (and even a little superstition) means that we often shy away from discussion of Alzheimer’s disease, instead joking (nervously) about “senior moments.” The reality is one we’d rather not dwell on.

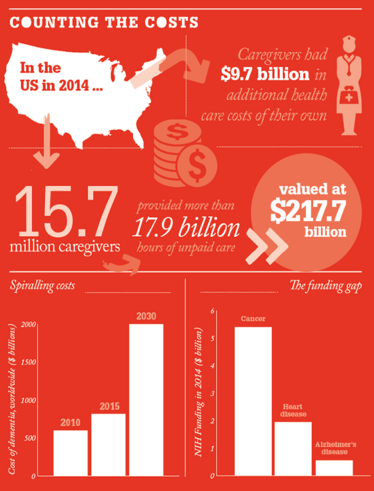

As the population ages, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are becoming increasingly hard to ignore. Already, Alzheimer’s is the sixth largest killer in America, and estimates from the Alzheimer’s Association put the number of Americans living with the disease at 5.3 million. Without a medical breakthrough to help prevent or slow the progression of the disease, this number will rise to 13.8 million by 2050 – with similar trends predicted across the Western world. That’s not just bad news for the millions of people affected directly or indirectly – it’s a huge challenge for already overstretched healthcare budgets, as shown in “Counting the Costs” below.

Alzheimer’s disease is already costing some countries hundreds of billions of dollars, but comparatively little research funding is being dedicated to finding treatments. The US government allocated federal funds of around $5.4 billion in 2014 to cancer research, and $1.2 billion for heart disease – while research on Alzheimer’s and other dementias came in at only $666 million. Director of the Massachusetts Institute for Neurodegenerative Disease, Bradley Hyman, who recently revealed another link in the chain of Alzheimer’s pathophysiology (here), admits that any scientist will say that their field does not receive enough funding. “But given the impact that Alzheimer’s disease will have on our society over the next 10 years, it is woefully underfunded. What is certain is that the cost of doing nothing is going to be immense.”

Perhaps the lack of obvious progress makes funding Alzheimer’s research a tough sell for results-focused politicians. After all, the history of the field is littered with failed drug programs, with only a few approved drugs on the market, none of which can prevent progression, only temporarily reduce symptoms. Why is it so hard to develop treatments for Alzheimer’s? Partly, it’s because we lack a complete understanding of how the disease develops on a molecular level, says Michela Gallagher, a Professor at Johns Hopkins University who will shortly be initiating a Phase III trial with the aim of slowing progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) into full-blown Alzheimer’s (here). “Much of the basic science has stemmed from genetic studies of inherited forms of Alzheimer’s disease, which make up only one percent of all cases,” says Gallagher, “but in fact the pathology may look quite different to the more common sporadic form of the disease. We know a lot about the complexity of the players in the brain, but not how they all fit together.”

While treatment remains elusive, researchers know more than ever before about how and why Alzheimer’s occurs. Our understanding is moving fast, and some of our initial assumptions are being proved wrong, according to Ewan McNay, who tells us about his pioneering work on insulin in the brain (here). Take amyloid plaques, one of the defining features of the disease since 1906 when Alois Alzheimer reported “a peculiar severe disease process of the cerebral cortex,” and still a diagnostic criterion for Alzheimer's disease today. It’s becoming increasingly clear that plaques may not be what is causing damage. In fact, they may be evidence of a self-defense mechanism – the brain’s attempt to sequester harmful extra amyloid protein. In other words, plaques are a sign – not a cause – of damage in the brain. So what is it that starts the descent into Alzheimer’s? Why is progression so unpredictable? And, above all, how can we stop it?

Many believe the answers now lie within our grasp. Author Terry Pratchett, who died aged 66 from a rare form of the disease, wrote in 2008, “I believe the D-day battle on Alzheimer’s will be engaged shortly and a lot of things I’ve heard from experts strengthen that belief. It is a physical disease, not a mystic curse; therefore, it will fall to a physical cure. There’s time to kill the demon before it grows.”

In the following articles, we speak with three scientists who are expanding our knowledge of Alzheimer’s – in the hope of one day defeating it.

Untangling Tau by Brad Hyman

The Overactive Brain by Michela Gallagher

Food for Thought by Ewan McNay

“As Editor of The Translational Scientist, I’m working closely with our audience to create vibrant, engaging content that reflects the hard work and passion that goes into bringing new medicines to market. I got my start in biomedical publishing as a commissioning editor for healthcare journals and have spent my career covering everything from early-stage research to clinical medicine, so I know my way around. And I can’t think of a more interesting, challenging or important area to be working in.”