Does Screening Save Lives?

Data from a large-scale trial suggest that screening cuts ovarian cancer mortality rates by 25 percent – but some remain skeptical

The UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) is one of the largest clinical trials ever conducted worldwide – 202,000 women in 13 regions across the UK are involved. The study estimates a 15–28 percent reduction in mortality attributable to ovarian cancer screening via annual blood tests for CA125 (1), but many have reacted with caution at this stage. We spoke with lead author Ian Jacobs, professor at University College London’s Department of Women's Cancer, to find out more.

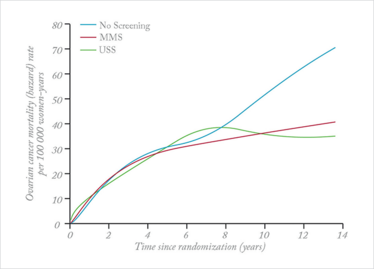

Ovarian cancer mortality rates with and without screening. MMS=multimodal screening. USS=ultrasound screening. Reproduced from (1).

What do the results tell us?

The findings provide the first evidence that the outcome of ovarian cancer can be changed through early detection by screening. The evidence is persuasive of a mortality reduction of the order of 25 percent, but is not yet conclusive. The pattern of results suggests that it will become conclusive over the next 2–3 years. Given that the outcomes for ovarian cancer are so poor (less than 40 percent five-year survival) and have remained largely unchanged for over 20 years, this is of great importance. What’s more, it seems likely that screening can be refined to bring even greater benefit, which could prevent the suffering and deaths of many thousands of women each year.

Tell us about the reaction from the community

Some have erred on the side of being overcautious of our results because the primary analysis did not reach significance. We had specified the Cox test as the primary analysis 15 years ago in the design of the study, so we had to use it. This was an unfortunate choice since it took 8–9 years before participants developed ovarian cancer and deaths started to occur. The impact of screening on mortality did not therefore start to appear until 10–14 years into the study.

In retrospect, a weighted analysis would have been a better choice, and indeed applying this analysis revealed a significant difference in mortality. Given that the results of the Cox test and the weighted analysis do not agree with each other, we cannot be absolutely certain that screening saves lives, but the findings are persuasive. We need to continue to follow-up the women who took part in the trial for another 2–3 years to be able to definitely confirm the mortality reduction.

What next?

Whilst awaiting longer-term mortality data, we are analyzing the health economics side of screening. Our group and others are looking at ways to target screening to medium- and high-risk groups and avoid screening low-risk groups. We are also working on novel blood tests, which we may be able to add to CA125 and the ROCA. I expect to see steady advances over the next few years, with large-scale screening rolled out within five years.

- I. J. Jacobs et al., “Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a randomized controlled trial”, The Lancet, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01224-6 (2015).

Professor at University College London’s Department of Women's Cancer.