Adaptive Invaders

New evidence suggests there’s more to metastasis than MMPs, demanding a therapeutic rethink.

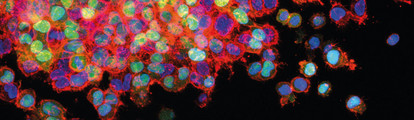

Metastasis is the most dangerous step in a cancer’s evolution, yet specific therapies intended to inhibit the process remain elusive. Scientists have long focused on inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) – a family of enzymes that are believed to aid cell migration by degrading the dense network of proteins – called the basement membrane – that surrounds human tissues. Now, a study reported in Developmental Cell suggests there may be far more to the story of metastasis than previously thought (1).

David Sherwood of Duke University is one of the papers authors. His team has been studying the invasive behavior of anchor cells in the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, which they have found invade like cancer cells. “What’s surprising is that we’d conducted many screens of invasive behavior in the worm, and we never identified MMPs as playing a key role – despite it being thought that they are absolutely critical to metastatic cancer invasion.”

The team set out to unravel the paradox by creating genetic knockouts of the six MMPs expressed in the worm. “The cells we studied still invaded – what is remarkable is that Laura Kelley [the paper’s first author] found that the invading cell adapts its invasion strategy,” explains Sherwood. “It forms a large battering ram – a structure made of F-actin, which never forms normally – to breach the basement membrane.” Mitochondria that fuel energy dependent processes in cells were also found to localize to the battering ram. Sherwood believes this adaptive invasion strategy might be why clinical MMP inhibitor trials failed in cancer patients. “Consider the basement membrane that surrounds all tissue – it emerged right at the time of animal multicellularity (approximately 700 million to a billion years ago),” he says. “Given how long that is in evolutionary terms – and the importance of crossing basement membranes – it's likely the mechanisms that allow cells to cross those kinds of barriers are ancient and conserved and are simply hijacked by metastatic cancer.”

According to Sherwood, however, the most exciting discovery might be something much more fundamental. “Our unpublished work suggests that the way that these invasive cells make proteins is unique,” he explains. “We think that because the cell has to make a lot of proteins in a very quick amount of time (the battering ram approach to invasion takes around 90 minutes and ‘traditional’ MMP driven invasion takes around 45 minutes), it has to use unique translation machinery.”

The longer-term goal for the team is to to identify additional ways in which cells may adapt their invasive program to the loss of MMPs. Sherwood believes this could have important application in the clinic. “We’re excited by combining different types of invasion inhibitors – for example targeting energy production in combination with MMPs. In particular, the ATP transporter we identify in our paper – Ant1.1 – could be a terrific candidate for therapy.”

- LC Kelley et al., “Adaptive F-actin Polymerization and Localized ATP Production Drive Basement Membrane Invasion in the Absence of MMPs.” Dev Cell, 18, 31084-6. [Epub ahead of print] (2019) PMID: 30686527