The Esophageal Balloon

The story behind an inflatable pill and a sensitive biomarker that pair up to improve screening for Barrett’s esophagus – and help prevent a highly aggressive cancer

At a Glance

- The preventable indicator of esophageal adenocarcinoma – Barrett’s esophagus – goes undetected in many patients

- The current gold standard for testing Barrett’s esophagus is endoscopy, which is expensive and time-consuming for patients

- A biomarker panel and a novel swallowable balloon may combine to offer an easier way to detect the condition

- Endoscopy could be a procedure primarily for identifying and treating patients with dysplasia.

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is the fastest-growing cause of solid tumor-related deaths among adult Americans, and, with a five-year survival rate of only 20 percent, it now accounts for more deaths than ovarian cancer. The best chance of reducing EAC deaths is to detect individuals who harbor Barrett’s esophagus (BE), a condition characterized by abnormal cell growth in esophageal epithelia that can be a precursor of EAC. BE can easily be treated when progression toward dysplasia is detected. The challenge? BE is frequently asymptomatic. Endoscopy can detect the condition, but such procedures are expensive and require the patient to commit a day of their time and to undergo sedation. And that’s why most individuals with symptoms of gastrointestinal reflux – a cause of BE – treat their symptoms with over-the-counter medication and don’t undergo endoscopy. Consequently, most BE cases remain undetected, leading to 90 percent of EACs being diagnosed in patients who were unaware they even had BE. Our group at Case Western Reserve University has a long commitment to finding a better solution, which we believe we achieved with our recent publication (1). The impetus for our project was to develop a biomarker panel and to invent a simple, patient-friendly sampling device that could replace the need for endoscopy.

The search for the right biomarker – and the right sampling tool

My group previously pioneered methylated vimentin exon 1 as a DNA biomarker for detecting gastrointestinal cancers, starting with colon cancer – a concept that became the Exact Science/LabCorp ColoSure stool DNA test. In 2012, we also published findings showing that methylated vimentin DNA is an even more sensitive and specific biomarker for detecting BE and EAC than it is for detecting colon cancers. We wanted a detection technique that could offer even greater sensitivity, leading us to identify cytosine methylation of CCNA1 DNA as a second marker of BE. Paired with the established methylated vimentin assay, the two-marker test provided over 90 percent sensitivity and specificity for BE detection. Having identified a robust analytical method, the next step was to work on replacing the endoscopy.

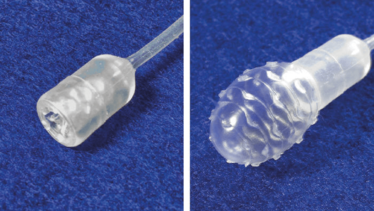

Our team of inventors – Amitabh Chak, Joseph Willis, and I – met with a team of industrial designers and brainstormed about how we could create a swallowable device to sample the esophagus. We considered dozens of different approaches, but as soon as the idea of a pill-sized balloon came up, we all jumped on it as the answer. We immediately realized that a balloon offered the opportunity to create a device that would be small and comfortable for the patient, but effective in sampling the esophagus. We then realized that if we encapsulated the balloon, we could gain additional benefits by being able to target sampling to just the lower esophagus, where BE develops – plus, we’d be able to protect the sample from dilution and contamination (by avoiding dragging the exposed balloon through the entire esophagus, throat, and mouth). Next, we had to optimize the surface texture of the balloon for collecting cells, which we explored first by using chicken skin and afterwards by testing pig esophagus explants. It took over a year to engineer something that worked, but once we had it in hand, the simplicity of the approach was truly alluring.

The technique’s high sensitivity and specificity led us to think it could be a first line of defense for screening individuals who have symptoms of gastric reflux, instead of undergoing endoscopy. Endoscopy could be reserved for individuals whose symptoms progress despite medical treatment for reflux. Moreover, we hope that the accuracy and cost-effectiveness of the test could allow it to be used to screen asymptomatic individuals, who would not be considered for endoscopy. Endoscopy would also be needed to follow up on a positive balloon test so as to distinguish standard BE from BE with dysplasia, which is closer to being cancer and is treated endoscopically by ablation or removal.

Carla Schaffer/Moinova et al./AAAS

More work to do...

We want to be able to identify all individuals who harbor BE in the most cost-effective way so as to facilitate surveillance and treatment as soon as it starts to progress. Ultimately, we want to stop anyone from ever developing EAC. To that end, we are currently working on the second generation of the balloon to make it even easier to swallow and even more effective in collecting cells. We’re also identifying biomarkers to distinguish between BE with versus without dysplasia.

In our current study, we tested many individuals who were already known to have BE – that is a standard way to investigate any new diagnostic test. Our next study will be designed to identify individuals with BE out of a general population studied in a national clinical trial at multiple centers.

It takes a multidisciplinary team to make such discoveries, and especially to translate them into practical advances for use in patients. We are lucky that at Case Western Reserve University and at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center we have such a team. Our work is truly the result of a team effort, involving gastroenterologist Amitabh Chak, pathologist Joseph Willis, molecular biologist Helen Moinova – and a medical oncologist and cancer geneticist (me).

We have also been fortunate to have tremendous support from the NIH, which has awarded us a Barrett’s Esophagus Translational Research Network (BETRNet) center, led by Dr. Chak and a GI Cancers Specialized Program of Research Excellence – GI SPORE that I lead.

Sanford Markowitz is the Markowitz-Ingalls Professor of Cancer Genetics, and Medical Oncologist and Colon Cancer Researcher at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Cleveland, USA.

- HR Moinova et al., “Identifying DNA methylation biomarkers for non-endoscopic detection of Barrett’s esophagus”, Sci Transl Med, 10, eaao5848 (2018). PMID: 29343623.

Sanford Markowitz is the Markowitz-Ingalls Professor of Cancer Genetics, and Medical Oncologist and colon Cancer Researcher, at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.