A Story of Shared Science and Solutions

Pharma companies are notoriously protective of their intellectual property, so it’s a big deal to open up and give knowledge away for free. Nevertheless, it is the path that LEO Pharma took with its Open Innovation platform – and we’ve learnt that, if you give a little away, you can expect much in return.

LEO Pharma’s open innovation project didn’t come about from someone saying ‘let’s do open innovation’. Instead, it stemmed from the recognition that we needed to do something different. Back then I hadn’t even heard of open innovation...

Curiosity has always been my personal driving force. Good things tend to come from being curious, whereas nothing will happen if you’re indifferent. My interest in science was an expression of my curiosity. I started out by focusing on physics, computers and electronic engineering, but then I decided that I wanted to apply it differently. I looked for something that was still scientific, but completely different to engineering and electronics. The answer was biology.

I had to twist my mind to get into biology, but I ended up with knowledge of molecular genetics, medical sciences, programming, robotics, mathematics and electronics. The combination steered me towards work in drug screening, and it was easy for me to jump into that position because of my interdisciplinary education. Interdisciplinary connections are really important for open innovation – and for future innovation. In the past, pharma has just done what pharma does best, which is to be very, very specialized. But that eventually leads to a dead end because it becomes very difficult to do more of something or to do it better. Eventually you have to start doing something different. I believe that open innovation models will lead to a big change in how we work.

I started at LEO in 2004 as a research scientist, later leading a team in molecular pharmacology. The company was investing a lot of resources in setting up what we call ‘disease-relevant’ screening. This isn’t target-specific because we aren’t screening chemicals to find something that works on a single protein target (reductionist approach); instead, we prefer the phenotypic drug discovery approach, which takes biological complexity into consideration. And rather than just focusing on one target, it opens us up to new and different discoveries.

I thought we could get more out of our investment in drug screening technologies and I decided that the solution was simply to test more molecules. Unfortunately, there are only so many compounds that you can manage in a rather small company, which is why collaborations are so common in pharma. Classical materials transfer agreements (also known as MTAs) – where you agree to test a technology partner’s compounds – are often preceded by months or even years of negotiations. Given the timeframes, I’m not sure if this approach significantly adds to the discovery pipeline. My feeling was that we needed to make it simpler to get more new molecules into the system so that we could fully leverage the potential of LEO’s proprietary models and assays, which we’ve invested a lot of time and money on. I believed that we could add throughput to drug discovery processes from external molecules, such as hits, leads, molecular probes, or even candidates.

At the same time, we were starting to become aware as a company that we needed more exposure of our name – which was hammered home when someone from a big pharma company said they’d never heard of us, even though LEO is a more than a hundred years old and employs about 5000 people globally! We suddenly realized that it doesn’t matter what you think of yourself – if no one knows about you, then you don’t exist – and ultimately it means that no one can work with you. To change that, we had to announce our presence, open up and offer something. So I had two main goals in mind: to increase the throughput in our model systems and to help make others aware of us. Open innovation interested me, but talking about open innovation is much easier than actually implementing it...

Fortunately, I met with a great person called Jonathan Lee from Eli Lilly. He introduced me to Lilly’s open innovation platform and I realized then that since other people were doing it, it was possible. After a major re-organization in our drug discovery operations, we made a strategic decision to “leverage external knowledge”, which evolved into a commitment to open innovation. It was new to us as a company – and a big step – but we knew that it must be done. I stepped out of science and began focusing solely on an open innovation platform. It required my single-minded focus because it was such a huge change – and challenge – for us. That was about two and a half years ago and I’ve been working on it ever since. Today, I am heading LEO Pharma’s open innovation initiatives in R&D.

Overcoming Catch-22

So, how do you go about setting up an open innovation platform? Once LEO had made the decision to embrace open innovation (with me as the project leader), I had to work out what to do next. LEO specializes in dermatology and we have a large number of approved drugs on the market for patients (we helped 48,000,000 patients in 2014). To aid us with our research efforts, we’ve also developed a range of very effective, phenotypic disease-relevant in vitro bioassays, which I’ve already mentioned. So the starting point was offering external collaborators the opportunity to test their compounds using our assays in an open innovation approach. A simple proposition but much easier said than done!

Open innovation is impossible without proper management endorsement, but even that is not enough on its own; open innovation is a big change and you can’t push it down people’s throats. I needed to do a lot of preaching to convince people of the vision and to create enough stakeholders to help me implement it. Of course, the natural reaction from most people being asked to change is “why?”. If you’ve been doing something that works for a hundred years then why change it? It’s hard to argue with that, so instead I had to focus on explaining why it was in people’s best interests to change by identifying the local benefits of open innovation for each department involved – and removing the obstacles of “extra work”.

I spent almost the entire first year drumming up support for the project. At times, it felt like I was in a Catch-22 situation – I needed to show people what the end result would look like in order to engage them, but at the same time we needed to work on it before we had a definition of the end result. I persevered, and gradually built up a practical and concrete picture of what we should do. At this stage, not everyone will get it – and you shouldn’t expect them too – focus instead on the small percentage that do understand the project and on those who can make all the difference to its success.

Pictured: Christine Brender Read, Manager In vitro Biology, OI role: Head of Assay operations; Birte Thoke-Jensen, Senior Technician, OI role: Assay development; Martin Stahlhut, Senior Scientist, OI role: Assay development; Peter Hansen, Senior Technician, OI role: Assay development; Jakob Felding, Senior Director, OI role: Head of Skin Research; Mette Skovgaard Bendsen, Principal Technician, OI role: Compound Management; Lone Moess, Senior Technician, OI role: Compound Management; Niclas Nilsson, Head of R&D Open Innovation, OI role: Strategy, design and implementation; Anne Caprani Winkel, Senior Technician, OI role: Data Management; Eva Hansen, Principal Technician, OI role: Assay development and execution; and Peter Scheipers, Senior Scientist, OI role: Science evaluation.

Let it go

Once you have your supporters, you need to address the practicalities, such as how to make open innovation accessible to external partners. In my case, I was asking how I could make it easy for others to test their chemical assets in our models. In particular, I wanted to reduce the time it takes to negotiate an MTA. But many problems popped up once I started exploring this topic, such as issues relating to disclosure of the science and the biological models we’ve developed. Disclosure is the key aspect of open innovation, but it is difficult for a traditional pharma company to accept. When you disclose, you open up, and when you open up, you give your competitors access to some of your knowledge – and potentially your intellectual property (IP).

Rather than focusing on the problems, I think it’s beneficial to think of what you are trying to accomplish. For example, if you need a drill, the normal approach is to consider the attributes you want – something mobile and sturdy – and design the best drill. But in reality, you actually need what the drill can do for you; for example, making a hole two meters up in a 10-cm thick concrete wall – and that should become the focal point rather than assuming that you need a drill. If you asked someone else to suggest a solution, they may come up with a different tool altogether. So in order to get access to those different and innovative solutions – e.g., novel molecules, mode-of-actions or targets – you have to disclose the science behind the models you are using and tell people what you are looking for.

For LEO, looking at what we wanted to accomplish helped us to focus on the barriers in a different light. To gain the trust of external collaborators, and to make it easy for them to work with us, full disclosure, openness, and maintaining security were key factors – we couldn’t debate that and so the question became, what do we need to do internally to make these things happen?

A long negotiation with our legal department ensued. The biggest problem was IP. I had to argue that we could not perform open innovation alone and that we needed to give something away in order to get something back – which is virtually unheard of in pharma. From a return of investment (ROI) perspective, it’s pretty hard to argue for open innovation!

Opening Up Big Pharma

Most Big Pharma companies have established some kind of open innovation platform. Some do not require compound structure to be submitted whereas others do. The rights to generated data can also vary.

- Eli Lilly’s open innovation platform is called OIDD (Open Innovation Drug Discovery). OIDD focuses on neglected and tropical diseases, diabetes and oncology. Researchers get access to computational design tools and can submit compounds for screening.

- AstraZeneca/MedImmune’s open innovation collaborations span target validation, pathway exploration and translation. The main areas of focus include cardiovascular, respiratory, oncology, inflammation and autoimmune diseases.

- Bayer offers financial support for small molecule drug development via its Grants4Leads initiative. The latest call for submissions is open until the 30 March 2016. The company also has a Grants4Apps initiative that focuses on supporting healthcare startups and developer teams.

- GlaxoSmithKline has established an ‘open innovation strategy’, which has a particular focus on the developing world. The company is involved in various open innovation activities. For example, in 2010, the company turned its Tres Cantos lab in Spain into an open lab. Projects from universities, not-for-profit partnerships, and other research institutes are chosen on a regular basis. GSK also has an open innovation platform dedicated to innovation in consumer healthcare.

Selling the idea internally had to be done step by step. At first, there was reluctance to disclose the secrets of our top biological assays, but now we tell everyone. It was a huge step, but as a result of that we will get access to innovation that we didn’t know existed. With our approach, we disclose information concerning our proprietary assays on psoriasis and eczema (human primary skin cells that we stimulate with cytokines to induce disease phenotype) and tell people how they work. The external researchers get access to our assays, but in return we get someone who says, “Wow! I work in oncology on protein X and I didn’t think it was relevant for psoriasis, but now that you say it could have a role I’m going to try it in your assay.” It could produce good results, which means that you have someone on the outside offering fresh innovation, which the pharma industry desperately needs. This kind of orthogonal innovation – where you get novel solutions from a field outside your usual sphere of engagement – is an important aspect of innovation, and open innovation might just be able to deliver it.

Disclosure is not the only topic that we had to discuss with the legal team – ownership of the data was another key issue. And we chose to give this up too, for the benefit of open innovation. An external partner sends us their compound to test with our assays; we perform the test, create the data and then we give the data back. The external partner now has ownership of the dataset and can use it as they please. We only ask to take it forward if we think it looks interesting – which is something that will always need negotiations.

Since we don’t have ownership of the data, our external collaborators can take the data to our competitor if they want. Not everyone is comfortable with the approach, but there are arguments in favor of it. Firstly, we are only giving away early discovery models – systems that only give indications that a particular molecule might be relevant for a given disease. Turning that knowledge into a commercial product is very complex, so really there is little value in what we’re giving up from a product perspective. And if a collaborator does decide to go to a competitor, we would know about it, we have seen the data, and it’s simply a discussion with a competitor. It’s not a real loss for us – the only loss we make is the costs of running the tests on those compounds, which is not significant in the bigger picture. When you break everything down like this, there aren’t really any problems – only opportunities.

And in fact, rather than trying to justify open innovation from a ROI perspective, you can talk about the opportunity for cost. What would it cost us if we didn’t have the opportunity to test this molecule? It would have gone to the competitor of course, without our knowledge.

We’ve also dispensed with the requirement for the external partner to disclose the chemical structure of their compound. This is for our benefit too – we don’t want people sending us information on chemical structures and then claiming in the future that we stole their invention – we still want to be able to work on our own chemical structures, even if someone accidently sent something similar to us. We only ask for an arbitrary name of the compound and the molecular weight, so that we can perform technical quality control.

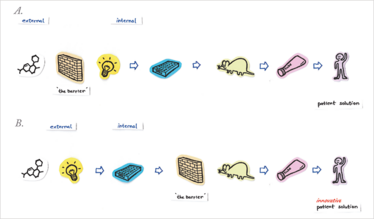

Traditional vs. Open Innovation Platform in Pharma Drug Research Process

Figure 1. How to go from an idea to patient treatment – the pharmaceutical drug R&D process simplified. A) Traditionally, a barrier exists to protect the confidential R&D tools, which makes it really hard for an external idea, in the form of a molecule, to enter the process. B) Open innovation can be implemented to enable evaluation of external opportunities. The barrier is moved to the right, effectively exposing the early R&D biology tools and allowing external partners access to them.

Breaking business barriers

No one uses an open door, if they don’t know that it exists. Once we had the plan for LEO’s Open Innovation platform we had to make sure people knew about it. We’ve got a web portal, but perhaps one of the main barriers in getting the research community to engage with open innovation is the way the term has been misused. Most “open innovation” platforms demand compound structures or other IP information that subsequently binds you to the pharma partner. Big pharma has a really bad reputation – we are the big, bad wolf and the public opinion seems to be that if we can steal anything, we will. Many of the researchers I’ve spoken to tend to feel that there is always a ‘but’ with a big pharma “open innovation”initiative, so not requiring compound information is a great way to create trust.

We’ve made it as easy as possible to get involved with our platform – all someone has to do is to download the PDF from the portal website (it’s a simplified legal framework document that is about protecting the external partner rather than us. I encourage you all to have a read). The collaborator signs the contract, writes down the compound and company name, and sends it in. We then countersign it and send it back, together with glass vials for the partner to transfer their compounds. The glass vials are marked with bar codes from our internal data management system – and they enter our processes just as our own internal compounds would. Within about eight weeks or so, we send a PDF report back to the partner. The report basically says, “Here is your data. You may use it in any way you like.”

Occasionally, we may say that we are interested in discussing the compound further and suggest exploring a more formal collaboration, which is when we proceed to legal agreements and negotiations. But the point of open innovation is to make it really easy to try something at the early stages. So, in our initiative, at first there are no business barriers or restraints, which allows our external collaborators to focus on the basic science. If we overlap, then we can talk business.

Innovating for patients

Our Open Innovation platform launched in March 2015. We haven’t been advertising the platform a great deal yet and there are still some tweaks to be made, but so far it’s been a great success. We’ve had around 15 open innovation partners (a mix of universities and companies) in the last year, and we’ve tested around 150 compounds. Three of those were interesting… and one of our open innovation partners works with targets that we didn’t even know existed, so through open innovation we now have access to compounds that target new molecules and proteins. And the real beauty is that the process is very scalable. We have the capacity to test many more compounds than we did during the past year – we deliberately kept a low profile during 2015 to give us room to make adjustments as we went along. But 2016 will be more about how we ensure that the Open Innovation platform evolves into an established, smoothly operating process.

Investigating Inflammation and Dermatology

LEO Pharma has a number of disease-relevant in vitro bioassays to help identify compounds that may have potential in inflammation and dermatology. But the exact assays used in the company’s Open Innovation initiative may vary – and are also under constant development.

Psoriatic inflammation in human keratinocytes

Primary human keratinocytes are stimulated using a psoriasis-specific cytokine cocktail that induces an inflammatory response measured as an increase in IL-8 secretion. Test compounds are tested for the ability to inhibit this inflammatory response.

Eczematous inflammation in human keratinocytes

Primary human keratinocytes are stimulated using an eczema-specific cytokine cocktail that induces an inflammatory response measured as an increase in CCL5 secretion. Test compounds are tested for the ability to inhibit this inflammatory response.

Human PBMC release of TNF-alpha

This ‘classic’ inflammatory assay uses primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) activated by lipopolysaccharides (LPS). The compounds are tested for the ability to inhibit LPS-induced TNF-alpha release.

IL17 release from human PBMC

Primary human PBMC are stimulated with CD3 and CD28 to release IL-17 and IFN-g. Cell viability is also measured to determine potential cytotoxicity. This assay is currently under development, but will be available for open innovation soon.

We are very lucky as a company. LEO is a foundational company, so we don’t have any shareholders and we don’t have to report to or give any money back to our owners. Perhaps that is why we could do things differently. I can only imagine what it must be like trying to explain the benefits of giving away something for free to shareholders! But there are huge benefits in learning to let go. I’d like to see more genuine open innovation projects in the industry, as it would help everyone in the pharma ecosystem.

Another exciting project that I am working on involves trying to engage patients in open innovation – the next step in developing the open platform. We are trying to create a community that can drive the science forward more effectively; an open source and open science community that will include industry, academia, biology, chemistry, patients and more. We actually have 10 anthropology students in Copenhagen looking into what it would take to engage patients in open innovation drug discovery research. And here we come back to the importance of being interdisciplinary, which is how I began this article. These students are getting patients to rate their treatment needs and to translate those needs into drug research properties, which may help us to find new molecules. Open innovation is not just about inviting universities and biotechs to bring us new molecules; it will also allow us to request molecules with particular properties that reflect what patients want – and that really is patient-centric.

Instead of innovating themselves, many large companies are buying pipelines. But what happens when there is nothing left to buy? I believe that pharma will increasingly need to rely on innovation from external partners – and we need interfaces that tap into external innovation. If it’s open then it is more appealing and inviting. And though it may sound bold, if pharma companies fail to adopt open innovation then one day they will surely suffocate. If you want to set up an open innovation project, I recommend that you learn to give a little – and you will gain a lot!

Niclas Nilsson is Head of R&D Open Innovation at LEO Pharma A/S, Denmark.

Other relevant personnel (not pictured in the article) were also involved in the Open Innovation project: Mikkel Svoldgaard Gadsboell, Director R&D Legal, OI role: Legal counsel and contracts; Tine Skak-Nielsen, Senior Principal Scientist, OI role: Assay development; Peter Bredekjaer Nielsen, Student Assistant, OI role: Operations; Lene Torp-Milojevic, Technician, OI role: Assay execution; Birgitte Davidsen, Senior Technician, OI role: Assay execution; Kathrine Abell, Senior Manager, OI role: Head of explorative biology; Lena Mårtensson, Senior Director, OI role: Business and Partnerships; and Thorsten Thormann, Vice President, OI role: Head of Research.

First published in The Medicine Maker (www.themedicinemaker.com), a sister publication of The Translational Scientist.

Niclas Nilsson is Head of R&D Open Innovation at LEO Pharma A/S, Denmark.