A Better AD Model

How primary neuronal cell cultures are unraveling the role of amyloid β oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease.

Fifty million people live with dementia around the globe – approximately two thirds of which suffer from Alzheimer’s disease. Driven by an aging population, this daunting figure is expected to exceed 152 million by 2050. The potential economic impact? The World Alzheimer Report 2018 makes for a worrying read: care for dementia currently exceeds $1 trillion a year – a figure that is forecast to double by 2030 (1). The report called for significant investment in the field and, in response, the G8 countries committed to developing a dementia cure or treatment by 2025. How? By collectively increasing funding for dementia research, calling for greater innovation, and recognizing dementia as a growing threat to global health.

Despite being described over a century ago, we are only now beginning to understand the molecular mechanisms that underpin AD pathology (2). In Alzheimer’s patients, abnormal aggregates of the protein amyloid beta (Aβ) – the hallmark of the disease – can be seen at the microscopic level (3); yet, the hypothesis that amyloid accumulation is the major cause of neurodegeneration has come under increasing scrutiny. Now, evidence suggests that prefibrillar soluble Aβ oligomers are more toxic to neurons, and inhibit many important neuronal activities that relate to the symtoms of AD (4).

Developing appropriate therapeutic agents to exploit this feature have proven challenging, however, as the biological and structural characteristics of Aβ oligomers and their formation mechanisms remain unclear. Recent evidence suggests that the size of Aβ oligomers is extremely variable (<10 kDa to >100 kDa), and that significant structural polymorphism exists, even for those oligomers of comparable size (5).

The quest for a cure

Treatments for AD have tended to focus on alleviating symptoms and slowing disease progression in the absence of a cure. Cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, are commonly prescribed for AD to increase levels of acetylcholine in the brain and to improve neuronal communication. As a second line of treatment, or in severe cases of AD, an NMDA receptor agonist – memantine – can be used to reduce symptoms by inhibiting excess glutamate production, which is toxic to the brain (6). As we’ve learned more about the biochemistry of AD, several new treatments modalities have entered the development pipeline; immune system recruitment, prevention of neuronal synapse degradation and enzyme inhibition have all be explored (7).

Less “direct” forms of treatment, for example cognitive stimulation, appear to improve memory, thinking skills, and quality of life – and may prove to be just as important as conventional therapies (6).

Many of these developments have been made possible using novel in vitro technologies to study previously impossible targets, such as muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, tau proteins and β-secretase enzymes. In addition, most of our knowledge of protein aggregation in AD has come from in vitro studies, despite the problems associated with the insolubility and high molecular weights of these fibrils. For example, in vitro studies of tau protein aggregation have revealed that short tau fragments aggregate faster than the whole protein and some hexapeptides play a key role in the formation of paired helical filaments, knowledge which could potentially lead to new therapeutic approaches (8).

Primary neuronal cells: a better model

Unlike finite or continuous cell lines, which can show genotypic and phenotypic variation because of serial passaging, primary neuronal cells isolated directly from donor tissue are able to better retain their in vivo characteristics. In vitro models based on primary neuronal cells are more physiologically relevant and are helping to uncover the role of Aβ oligomer species in AD. For example, primary rat cortical neurons have been used to examine the effect of Aβ oligomers on neuronal cell viability and apoptosis (9). In a study conducted by Pennington Biomedical Research Center, primary cortical neurons exhibited a dose-dependent increase in cell death after exposure to Aβ oligomers for 24 hours. This cell death was associated with an increase in reactive oxygen species and JUN kinase activation. Inhibition of JUN kinase activation alleviated this toxicity, which suggests a mechanism for treatment (10). A 2014 collaborative study has elaborated on this toxicity, demonstrating the different effects of monomers and oligomers in AD pathology in both a mouse cortical neuron cell line and a human neuroblastoma cell line. Aβ42 monomers were found to inhibit apoptosis. In contrast, Aβ42 oligomers were found to favor the formation of a complex involved in apoptosis.

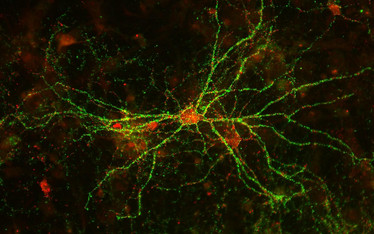

Figure 1: Cryopreserved rat cortical cells following 21 days in culture. Immunostained with anti-vGlut 1 (green); anti-vGAT (red) (© Lonza, Basel, cat.# R-CX-500.)

With growing evidence identifying Aβ oligomers as a potentially toxic agent in AD, there is considerable interest in developing therapies to reverse their effect. In 2017, researchers in Japan showed that reversing neurotoxicity induced by Aβ oligomers may be possible. In the study, primary cortical neurons were exposed to a two-day regime of Aβ42 oligomers, followed by a withdrawal period, during which Aβ oligomers were removed from the medium. Treatment with Aβ42 oligomers resulted in biochemical and immunocytochemical responses that were considerably attenuated following Aβ oligomer removal, suggesting the aberrant effect of Aβ oligomers could be reversible – with important implications for the development of AD therapies (11).

The interaction of Aβ oligomers with other molecules or neuronal cells has also been studied using primary hippocampal rat neurons. In one study, in vitro cultures of rat brain cells facilitated the identification of small molecules that block or prevent the binding of Aβ oligomers. These small molecules were then shown to prevent cognitive deficits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (12). The transmission of Aβ42 oligomers from neuron to neuron has also been examined. Fluorescently tagged oligomers were introduced into individual neurons and the spread of oligomers from neuron to neuron was observed (13).

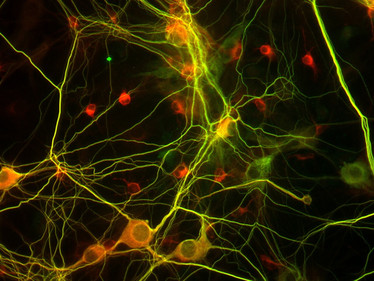

Figure 2: Cryopreserved rat hippocampal neurons, thawed, cultured (14DIV) and immunostained with anti-Map2 (© Lonza, Basel, cat.# R-HI-501)

The study of exosomes (small extracellular vesicles of endosome origin) in both the metabolism and aggregation of AD-associated Aβ protein has recently been established (14). Exosomes contain machinery to synthesize, degrade and induce aggregation of Aβ but it remains unclear if these factors increase or decrease the deleterious actions of Aβ (14). In 2013, An and colleagues showed that proteins on the surface of exosomes were able to interact with amyloid-beta assemblies and abrogate their detrimental effect on neurons in anesthetized rats (15). In another study, primary rat cortical neurons were used to study the effects of extracellular vesicles isolated from patient cerebrospinal fluid and mutant cells on cell viability. The researchers found that these vesicles contained more Aβ42 peptide and were able to induce degeneration of cerebral cortical neurons (16).

The ability to produce more physiologically relevant in vitro cultures of primary neuronal cells has been fundamental in advancing our understanding of neurodegeneration. Recent research involving these cell lines has helped us uncover the molecular mechanisms involved in the development of the disease. In particular, primary cells have helped to identify the role of Aβ oligomers in neuronal toxicity and cell death. Future research using primary neuronal cell models will help to increase our understanding of the formation of these oligomers, as well as their role in AD, and could aid in the identification of new treatment targets, moving us closer to curing this debilitating disease.

- C Patterson, Alzheimer’s Disease International, London, “World Alzheimer Report 2018: The State of the Art of Dementia Research: New Frontiers” (2018).

- J Parkinson, “An essay on the shaking palsy. 1817”, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 14, 223 (2002). PMID: 11983801.

- CL Masters et al., “Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome”, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 82, 4245 (1985). PMID: 3159021.

- M Sakono, T Zako, “Amyloid oligomers: formation and toxicity of Ab oligomers”, FEBS J, 277, 1348 (2010). PMID: 20148964.

- M Stefani, “Structural polymorphism of amyloid oligomers and fibrils underlies different fibrillization pathways: immunogenicity and cytotoxicity”, Curr Protein Pept Sci, 11, 343 (2010). PMID: 20423295.

- Alzheimer’s Research UK, (2017).

- Mayo Clinic, “Alzheimer’s treatments: What’s on the horizon?” (2019).

- S Barghorn, E Mandelkow, “Toward a unified scheme for the aggregation of tau into Alzheimer paired helical filaments”, Biochemistry, 41, 14885 (2002). PMID: 12475237.

- P Calissano et al., “Apoptosis and in vitro Alzheimer disease neuronal models”, Commun Integr Biol, 2, 163 (2009). PMID: 19513272.

- PJ Ebenezer et al., “Neuron specific toxicity of oligomeric amyloid-β: Implications for JUN-kinase and oxidative stress”, 22, 839 (2010). PMID: 20858948.

- D Tanokashira et al., “The neurotoxicity of amyloid β-protein oligomers is reversible in a primary neuron model”, Mol Brain, 10, 4 (2017).

- NJ Izzo et al., “Alzheimer’s therapeutics targeting amyloid beta 1-42 oligomers I: Abeta 42 oligomer binding to specific neuronal receptors is displaced by drug candidates that improve cognitive deficits”, PLoS One, 9, eCollection (2014). PMID: 25390368.

- S Nath et al., “Spreading of Neurodegenerative Pathology via Neuron-to-Neuron Transmission of Amyloid”, J Neurosci, 32, 8767 (2012). PMID: 22745479.

- LJ Vella, AF Hill, and L Cheng, “Focus on Extracellular Vesicles: Exosomes and Their Role in Protein Trafficking and Biomarker Potential in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease”, Int J Mol Sci, 6, 17 (2016). PMID: 26861304.

- K An et al., “Exosomes neutralize the synaptic-plasticity-disrupting activity of Aβ assemblies in vivo”, Mol Brain, 6, 47 (2013). PMD: 24284042.

- E Eitan et al., “Extracellular vesicle-associated Aβ mediates trans-neuronal bioenergetic and Ca2+-handling deficits in Alzheimer’s disease models”, Aging Mech Dis, 2, 16019 (2016). PMID: 27928512.

Product Manager, LPB-Bioscience Solutions, Lonza, USA